Ethos and Critical Discourse Analysis: From Power to Solidarity

Abstract

Works within Critical Discourse Analysis tend to concentrate on the analysis of institutionally reproduced power by dominant groups in society. Furthermore, focusing on negative or exceptionally serious social or political events results in the transition of the object of inquiry from the use of power to the abuse of power or at least its socially negative consequences. Therefore, and despite the explicit aim of siding with non-dominant groups in society, Critical Discourse Analysis focuses solely on the discourse of dominant groups, paradoxically leaving the discourse on non-dominant groups underexposed. Borrowing from French and Argumentative Discourse Analysis, the article proposes the co-optation of the concept of ethos in order to alleviate this problem. Specifically, ‘solidarity in discourse’ is presented as a useful approach to ethos within a Critical Discourse Analysis framework. As an illustration of the concept of ‘solidarity’ in discourse, the article presents an analysis of two texts from a very different interdiscursive tradition: a military statement by the Zapatista guerrilla (EZLN) and a newspaper column by the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez.

Keywords:

Critical Discourse Analysis, Ethos, French Discourse Analysis, Argumentative Analysis, Solidarity in discourse, EZLN, Chávez (Hugo)

Résumé

Les études effectuées dans le cadre de la Critical Discourse Analysis (l’analyse critique du discours) ont tendance à se concentrer sur l’analyse du pouvoir reproduit institutionnellement par des groupes dominants de la société. En outre, le fait de mettre l’accent sur des événements sociaux ou politiques négatifs ou exceptionnellement graves aboutit à déplacer l’objet d’étude de la question de « l’utilisation » du pouvoir vers celle de son « abus » ou du moins de ses conséquences sociales négatives. Malgré l’objectif explicite de soutenir des groupes non dominants de la société, la Critical Discourse Analysis se concentre donc uniquement sur le discours des groupes dominants, laissant paradoxalement le discours des groupes dominés sous-exposés. S’inspirant de l’analyse de discours (française) et de l’analyse argumentative de discours, cet article propose la cooptation de la notion d’ethos afin d’aborder cette question. Plus précisément, la « solidarité dans le discours » est présentée comme une approche utile de l’ethos dans le cadre de la Critical Discourse Analysis. Illustrant la mise en place de la notion de « solidarité » dans le discours, l’article présente une analyse de deux textes provenant d’une tradition interdiscursive très différente : un communiqué militaire de la guérilla Zapatiste (EZLN) d’une part et une chronique journalistique du défunt président vénézuélien Hugo Chávez d’autre part.

Introduction

Since the publication of Norman Fairclough’s Language and Power in 19891, scholars from diverse backgrounds have gradually gathered around the framework of Critical Discourse Analysis. Its practitioners share, on a methodological level, an explicit multidisciplinary focus, mainly bridging the humanities with the social sciences. The roots of Critical Discourse Analysis can be found in Rhetoric, Text Linguistics, Anthropology, Philosophy, Socio-Psychology, Cognitive Science, Literary Studies, Applied Linguistics and Pragmatics2. Additionally, leading Critical Discourse Analysis academics seem to specialise in specific types of discourse, particularly advertisement, media and institutional discourse, including politics. Often scrutinised topics are social-discursive phenomena such as sexism, racism, globalisation and, on a more abstract level, ideology. Critical Discourse Analysis should not be considered as a ‘school’ in the academic sense of the word, but rather a programmatic approach to language.

In practice, these common areas of inquiry come down to a strong emphasis on the concept of power. The overwhelming majority of works within Critical Discourse Analysis present an analysis of the use of power by dominant groups in society. The other side of the coin, however, is mostly left underexposed, namely the discourse of the dominated groups and of groups defying ‘hegemony’. In other words, the efficiency of the ‘rethor’in Critical Discourse Analysis seems to be deduced from his or her institutional position (authority), much in accordance with Pierre Bourdieu’s theories3. Pragmatists and discourse analysts from the French speaking world, e.g. Oswald Ducrot, Dominique Maingueneau and Ruth Amossy4, grant more importance to the discourse itself in the creation of the image of the orator5, known as ethos. Claiming an Aristotelian pedigree, the authors put ethos at the centre of the efficacy of discourse. Although the ‘sociological’ as well as the ‘rhetorical’ traditions clearly have a different focus, there is potential for a more complementary approach. In the same vein, we propose the co-optation of the concept of ethos in Critical Discourse Analysis in order to alleviate the aforementioned blind spot towards the discourse of non-dominating groups.

Power in Critical Discourse Analysis

The origins of Critical Discourse Analysis date back to the Thatcher era in Great Britain, within the context of the dismantling of the Welfare State, the frontal attack by the state on the power of workers’ trade unions and the growing colonisation of social life by commercialisation. Under such circumstances, it was clear that the triumphalist dominant discourse required the attention of the critical analyst. The following years were characterised by a wave of racism throughout Europe, institutionally translated in the success of extreme right parties and the normalisation of part of their discourse, and an overwhelming prevalence of a globalist discourse6 smothering democratic debate in the mass media. Focusing “upon a social wrong, in its semiotic aspect7”, as Fairclough coined it, seemed to have become a necessity.

Within Critical Discourse Analysis there are several research strategies with a very different theoretical and methodological background. The more prominent ones are Ruth Wodak’s and Martin Reisigl’s Discourse-Historical Approach, Gerlinde Mautner’s Corpus Linguistics Approach, Theo van Leeuwen’s Social Actors Approach, Segfried Jäger’s and Florentine Maier’s Dispositive Analysis, Teun van Dijk’s Sociocognitive Approach and Norman Fairclough’s Dialectical-Relational Approach8. A common trait among them is the attention to the dialectic relationship between discourse and social structure. This connection is linguistically explained by calling upon social theories about power and ideologies, mainly Michel Foucault’s ‘orders of discourse’ and ‘power/knowledge’, Antonio Gramsci’s concept of ‘hegemony’ and Louis Althusser’s ‘ideologicalstate apparatuses’. In an explicit attempt to overcome the risk of ‘structuralist determinism’, Critical Discourse Analysis assumes that discourse is at the same time socially constructive and a social construct9. Often cited authors to back this claim are Pierre Bourdieu (Language and Symbolic Power), Jürgen Habermas (Theory of Communicative Action) and Anthony Giddens (“Theory of Structuration”).

The theoretical canon indeed suggests the existence of a bias towards institutionally reproduced power as a defining characteristic of Critical Discourse Analysis, programmatically translated as the “common interest[s] in de-mystifying ideologies and power10”. As Jan Blommaert correctly observes, “[i]n general, power, and especially institutionally reproduced power, is central to CDA [Critical Discourse Analysis]11”. A common trait in Critical Discourse Analysis – which can also be observed in French Discourse Analysis – is that often “studies tend to be confined to situations where relationships are based on formal positions of authority, or where expertise and power gradients are clear, as with doctors and patients or teachers and pupils12”.

A second characteristic – a consequence of the focus on institutional power – of Critical Discourse Analysis is an overwhelmingly problem-oriented approach. Although often explicitly refusing to limit the object of study to negative or exceptionally serious social or political events13, in practice this kind of approach results in the transition of the object of inquiry from the use of power to the abuse of power or at least its socially negative consequences. In a work preceding Critical Discourse Analysis by a few years, Van Dijk delimits much of what later became its core program:

The bias towards institutionally reproduced power combined with a problem-oriented approach, unintentionally leads to a problem of ‘voice’. Blommaert aptly paraphrases Dell Hymes definition of voice “as the ways in which people manage to make themselves understood or fail to do so15”. Hymes relates voice to the “freedom to have one’s voice heard, freedom to develop a voice worth hearing16” and he states that “[c]ertain voices are acceptable, even valued, in certain roles, but not others17”. Although these approaches explicitly take sides with non-dominant groups in society, they paradoxically solely focus – albeit critically – on the discourse of dominant groups, leaving the discourse of the out groups out of consideration. Their voice may be present, but it is often limited to a weak echo, a perspective at best, and is rarely explicitly and manifestly present.

Ethos and Analyse de discours

Ethos is a concept borrowed from classical Greek Rhetoric. Isocrates, followed later by rethors in ancient Rome, defined ethos as a pre-existing given based on the moral and institutional authority of the speaker, such as reputation and social status. For Aristotle, however, ethos was rather conceived as an intra-discursive image: “trust must be the effect of discourse, not a bias about the character of the orator18”. Ethos was part of the wellknown rhetoric modes of persuasion along with logos (discourse and reason) and pathos (emotion activated in the audience).

A modern pragmatic-semantic notion of the Aristotelian ethos, as proposed by Maingueneau, is prevalent in French Discourse Analysis. The extra-textual character of ethos, in the tradition of Isocrates, is echoed in the notion of prediscursive ethos (‘prior ethos’), although less relevantly. According to Maingueneau, “the speaker does not express himself solely by a [social] role or position, he also lets himself be understood as a voice and a body19”. This concept of ethos closely ties in with the notion of ‘scene of enunciation’ (scène d’énonciation): “the utterance occurs in a created space, defined by the genre of discourse, but also by the constructive dimension of discourse20”.

Ruth Amossy’s Argumentation Analysis is closely related with French Discourse Analysis and it shares many of its notions and theoretical premises. Its merit, for the aim of this article, is its explicit attempt to reconcile Bourdieu’s theory of Language and Power with pragmatic views of illocutionary force such as Ducrot’s and Maingueneau’s21. For this undertaking, Argumentative Analysis promotes prior ethos to a full-fledged element of the analysis and a potentially decisive factor in the efficacy of the creation of the self-image of the orator22. The dynamics between the prior and discursive ethos – a dialogue – offers an opportunity to break with a social deterministic view of discourse:

A recent evolution in Amossy’s work makes her approach more compatible with Critical Discourse Analysis. While explicitly claiming the descriptive nature of Argumentative Analysis in the past (“Argumentative Analysis does not set out to denounce ideological biases, nor does it put on trial politically incorrect texts. It aims at describing, not at judging24”), she is not as categorical in her recent work. In a recent article Ruth Amossy and Roselyne Koren give an overview, limited to the French-speaking world, of the research of argumentation in the analysis of political discourse. Although not providing an answer, the genuine open question presented to the reader is in itself revealing: “[M]ust political discourse analysis be purely descriptive or in the contrary also normative; does it have to stay neutral or must it be guided by ethical principles that lead to critique, and even some times to denunciation?25”.

Ethos and Critical Discourse Analysis

In a book published in 2012 about political discourse, Isabela and Norman Fairclough formulate an answer, probably without being aware of the aforementioned question26: “We view evaluation of argumentation as an appropriate grounding for normative critique and explanatory critique (including critique of ideology)27”.

The authors share Amossy’s and Koren’s starting point, namely the fundamentally argumentative and deliberative nature of political discourse. What is more, ethos, within the French Discourse Analysis tradition, can be effectively applied to analyse institutional power in discourse very similarly to what Critical Discourse Analysis studies do without the notion of ethos28. This kind of modus operandi of ethos in Critical Discourse Analysis is useful, but would not help our aim to broaden the focus of Critical Discourse Analysis to the discourse of the – at least partially – dominated.

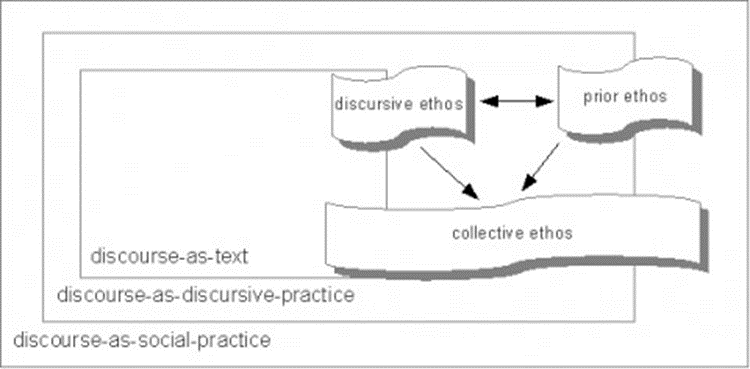

In the French tradition of discourse analysis, ethos is clearly a multi-layered concept. Maingueneau distinguishes prior and discursive ethos, closely tied to a scene of enunciation with a clear social aspect. Amossy gives attention to the notion of collective ethos as “a way which the I is extended and amplified to offer a group image29”. Furthermore, ethos is fundamentally a social/discursive hybrid notion. It is a “socially evaluated behaviour that can not be understood outside of a specific communicational situation, itself integrated in a specific socio-historical conjuncture30”. Mapping the concept to the three dimensions in the analysis of discourse as often conceived in Critical Discourse Analysis31 opens up possibilities far beyond a strictly text-linguistic stance.

Linguistic features and organisation in concrete instances of discourse are found in the discourse-as-text dimension: vocabulary, grammar, cohesion and text structure. In Norman Fairclough’s view, these terms can be understood as ascending in scale, accordingly “vocabulary deals mainly with individual words, grammar deals with words combined into clauses and sentences, cohesion deals with how clauses and sentences are linked together, and text structure deals with large-scale organizational properties of texts32”. As pointed out before, at this level ethos as such does not bring many new elements to the linguistic toolbox of Critical Discourse Analysis. Nevertheless, the reconstruction of the discursive ethos does bring coherence by grouping the findings at this early stage of analysis. While some linguistic features will inadvertently be applied by the orator, some will be very consciously put forward. This bundling of disparate linguistic features can reveal part of the argumentative strategy of the orator.

The second dimension in the analysis is discourse-as-discursive-practice. This is the dimension where discourse is produced, distributed and consumed in the social space, including interdiscursivity (the heterogeneous origin of the constituent elements of a text, including genre) and intertextuality (reworking of specific texts). As Amossy puts it, “prior ethos, and the discursive ethos that integrates and reworks it, are related to the authority derived from an exterior institutional status33”. It is at this stage that much of the dynamic between prior and discursive ethos happens. The dependence on the institutional authority is important, but by no means absolute. A speaker from a dominated group, or with a low social position, will have the task to overcome a less advantageous prior ethos (by example the lack of institutional power). In order to do this, the orator must show his solidarity with the audience to gain credibility, not only at the time of the utterance, but also by choices and actions external to it.

In order to progress to the next stage of discourse as seen in Critical Discourse Analysis, we need to take a detour through the notion of doxa. As an inheritance from their Aristotelian roots, doxa is a common concept in French Discourse Analysis and especially important in Argumentative Analysis. Doxa holds a similar place in these schools of discourse analysis as ideology or hegemony in Critical Discourse Analysis34. Chaïm Perelman defines doxa as follows:

Ethos itself is closely tied to doxa. The orator, when creating a self-image, needs to activate latent stereotypes36 as part of the argumentation and at the same time adapt his discourse to the expectation of the public in a determined setting. Doxic elements, including stereotypes, are “the ingredients of a dynamic interaction that could not develop without pre-existing points of agreement and consensual views37”.

In L’argumentation dans le discours,a seminal work within Argumentation Analysis, Amossy contrasts her notion of doxa with Barthes’ view on doxa as mystification38. She writes:

The downside of the concept of doxa, at least in Argumentative Analysis, is the static character in the social field. Doxa appears to be treated as a deus ex machina and ideology is removed from the range of discourse, instead of being placed at the centre of it. Alternatively, doxa, in order to be integrated in Critical Discourse Analysis, could be seen as a momentary and unstable result of the struggle for ideological hegemony and, at the same time, the target for discourse. This (attempted) change in hegemony could then be accessed through the angle of interdiscursivity and intertextuality: “The way in which discourse is being represented, re-spoken, or re-written sheds light on the emergence of new orders of discourse, struggles of normativity, attempts at control, and resistance against regimes of power40”.

Thus, re-evaluating doxa as a state of ideology permits us to integrate ethos, in its close relation to doxa, in the third dimension of discourse according to Critical Discourse Analysis: discourse-as-social-practice. This stage accounts for the ideological effects and hegemonic processes related to discourse. The transfer of ethos to the public and its transformation into a collective ethos goes beyond persuasion by constructing a social reality: “it [collective ethos] tries to mobilise the audience by leading it to adhere to a specific image of the community41”. The successful creation of a collective ethos over a period of time by the consistent reworking of the prior ethos reinforces the group identity and a particular ideology. More specifically, a class or group is considered to be hegemonic when it presents itself as realising the broader aims of the population42. This contribution of the collective ethos to a new social reality leads to questions about legitimacy and the struggle for power.

Ethos and solidarity

‘Solidarity’, which we define as a “loyal agreement of interests, aims, or principles among a group43”, has the potential to broaden the object of inquiry of Critical Discourse Analysis. For the reasons we presented earlier, Critical Discourse Analysis embraces a problem-oriented approach to discourse analysis. Notwithstanding, not all discourses that an individual analyst acknowledges as important or interesting can be considered a “social wrong”. What is more, a “social wrong” suggests the existence of a “social right”: discourse can be emancipatory or at least contain emancipatory elements. Recent and not recent evolutions around the globe entailed many successful discourses, often marginalised in the past. Some discourses disappeared as fast as they took the stage, but managed to reach a global audience, while other discourses became locally mainstream when the movements they originated from gained state power. Dominated groups, having their voices heard, open a window of opportunities for social change: those groups successfully resisted, rejected and transformed dominating discourses. An opportunity-oriented approach within Critical Discourse Analysis recognises the importance of the discursive processes of attempts for social change.

However, this does not imply a rejection of the importance of (institutionally reproduced) power in discourse. The reasons for the core position of power in discourse are still valid: all discourses are not created equal – or equally. The mere existence of dominated groups underlines the relevance of power within a framework of analysis: it is still the task of the analyst to identify pre-discursive and discursive marks of authority that play a part in the creation, distribution and consumption of texts and their social consequences. Furthermore, in the social world, discourses have varied constituents, with complex sources of authority and mixed relations to it. Hegemony is volatile, and discourse, following Foucault, “is not simply that which translates the struggles and the systems of domination, but for what, and through what one struggles, the power which one seeks to capture44”. The inclusion of the adjective ‘loyal’ in the definition of solidarity hints at the problematic relation with views on discourse analysis as being purely descriptive. The tentative opening of Amossy and Koren for widening (political) discourse analysis beyond a purely descriptive stance, is much in line with the prevalent practice of Critical Discourse Analysis. Evaluating the ‘loyal’ component of solidarity requires a level of interpretation in the analysis. Furthermore, as Fairclough points out, “[d]escription is not as separate from interpretation as it is often assumed to be. As an analyst (and as an ordinary text interpreter) one is inevitably interpreting all the time, and there is no phase of analysis which is pure description45”. As such, solidarity in discourse involves more than the simple adaptation of a successful rethor to the doxa of his public.

Illustration

In order to illustrate our view on ‘solidarity’ in discourse, we selected two examples that also reflect the heterogeneous character of power in discourse. The first example is an extract from a statement by the Mexican EZLN46 (National Liberation Zapatista Army). On January 1st, 1994, the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect, the Zapatistas (as the EZLN is known worldwide) declared war on the Mexican government. NAFTA resulted in the rapid acceleration of neoliberal economic policies that up to that point had impoverished the popular classes in Mexico and in the rest of the Latin America. Although deployed by an armed guerrilla movement, most actions of the Zapatistas were defensive and/or non-violent. Their rather fuzzy discourse and image entered popular culture far beyond the Mexican borders. The Zapatista discourse was rapidly embraced by a young anti-globalisation movement, mainly in Western Europe and the United States. The excerpt from the Zapatista communiqué is presented below:

The second example is a fragment from a newspaper column series “Las líneas de Chávez” (The [written] lines of Chávez) by the late left-wing Venezuelan president. In 1989 the Venezuelan government sent in the Army to dissolve growing popular protests against the price rises of oil-based products (including transportation and cooking fuel) and other drastic neoliberal policies. Hundreds of protesters were killed in the streets of Caracas (thousands according to Human Rights groups) then dumped in mass graves. This sad episode not only discredited the political system but was also of crucial importance for later events submerging the Army in a deep ideological crisis (Venezuela did not experience the far-right military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s as most of the continent did). The massacre, known as the Caracazo, was the main justification given by Chávez for his leading role in the 1992 military insurrection. After two years of incarceration for the failed coup, Chávez was pardoned. Running on a platform campaigning against the neoliberal socio-economic policies and for a new more democratic constitution to end the exclusive two-party parliamentary system48, he was elected president in 1998 with an absolute majority of the votes. The analysed fragment is included below:

Because of space limitations, we will not transpose to this paper the complete analysis according a methodology within a Critical Discourse Analysis framework50. Also, in order to be concise we will focus on the levels of discourse-as-discursive-practice and discourseas-social-practice.

In the Zapatista text – the first one we presented –, we can witness a delicate construction of multiple and indexed ethè. Although nowhere explicitly named, one ethos applies to Subcomandante Marcos, the well-known and eloquent non-Amerindian spokesperson of the Zapatistas. His ethos is absorbed in a timeless collective ethos of the indigenous populations of Mexico. “We” is not the EZLN but the pre-Columbian people of Mexico and it is inclusive enough to encompass even the potential sympathetic “fair skinned” reader. Chávez, in his writing, reinforces the ethos of a “man of the people” reminding the reader of his humble rural origins (in Sabaneta) and of the Christian background of his youth. In parallel, there is a subtle reinforcing of his ethos as an outspoken sympathiser of women’s rights and feminism in a cultural context of widespread sexism: the wisdom is not his; he recollected it from his grandmother, the Marxist theorist, activist and feminist Clara Zetkin and the revolutionary icon Rosa Luxemburg.

Despite the texts’ rather poetic language, both are ‘down to earth’. The vocabulary and the themes ring close to home to their direct public. Furthermore, both texts break radically with the conventions of genre. The texts are far from the expectations for, respectively, a military statement and a text from the head of state. As we have pointed out before, ethos is closely tied to doxa. The description of traditional indigenous people and their thinking in the Zapatista text are doxic. A common view on Amerindians is the one portraying them as powerless and resigned victims, impoverished, with strong ties to the land and a longing for a lost past. While never explicitly contradicting the doxa, the text implicitly turns the tables, nota bene on the day of the 502th anniversary of the conquest of America. The statement is not signed by the Mexican mestizo Marcos, often wrongly portrayed as the highest Zapatista authority, but by the CCRI-CG51 (Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee-General Command). The military structure of the EZLN is subordinated to the CCRI-CG, which in turn has the function of being the relay to the indigenous people and is as such subordinated to the indigenous community assemblies. Notably, it is an indigenous voice that absorbs the mestizo and accepts the reader as a brother in their midst, skin colour and language notwithstanding. Marcos himself, known for wearing a mask when speaking to the media, is presented as nameless and faceless. To become indigenous means leaving a non-indigenous past behind and completely blend with the collective, joining the faceless and powerless. The text reflects a sad irony, despite the dramatic social conditions in rural Mexico, through a game of mirroring and opposing formulas presented in the text52. Furthermore, the use of personal pronouns (he-his-we-us) is applied incoherently enough to cause confusion, probably on purpose. Also, a ‘grand narrative’, as one would expect from a left-wing guerrilla movement, is not manifestly present. These traits could be seen as conscious interdiscursive references to post-modernism53.

In the excerpt from Chávez the power relations are understandably different. The discourse of the political and social movements around Chávez experienced the transition from being marginal and/or oppressed and completely excluded from the political system, to the discourse of the state. While legitimised by consecutive democratic elections resulting in an absolute majority, the discourse of the Chávez government clashed with the discourse of conservative generals, industrials, trade union leaders54, high clergymen and most of the Venezuelan private media that controls most of the television broadcasting stations55. Abroad, Chávez’s antagonistic rhetoric became a recurring target for conservative media. This was often the case for discourse concerning the rejection of neoliberal policies of international institutions like the International Monetary Fund or the consistent effort for the economic and political unification of Latin America independently from the United States56. The conquest of state power reflects the success of Chávez’s discourse, although until today it is often defensive: its detractors and their discourse (through the private mass media) are still very influential and often dominant. In a country with an extreme conservative ecclesiastic hierarchy, doxic elements regarding religion often have conservative contents. In this example, Chávez’s ethos as a Christian is activated to emphasize the progressive and liberating aspects within the Catholic tradition. In a light, but serious style, the president links popular wisdom (“Mama Rosa”, his grandmother), with the progressive catholic Liberation Theology and Rosa Luxemburg’s revolutionary socialism exclusively through the words of women. Similarly to the Zapatista text, doxic elements are not directly contradicted, but transformed. Interdiscursively, we hear the call of “liberté [as in “Redeemer of the oppressed peoples”], égalité et fraternité” of the radical Enlightenment philosophers57, which laid the basis for the modern view on democracy and Human Rights58.

Conclusion

We introduced the notion of ‘solidarity’ in discourse in order to alleviate a paradox in Critical Discourse Analysis where its practitioners explicitly take up the defence of dominated groups in society while at the same time ignoring their discourses. To accomplish this, we argue for a bridge between the paradigms of Critical Discourse Analysis on the one hand and the one of French Discourse Analysis and Argumentative Analysis on the other.

From French Discourse Analysis and Argumentative Analysis we co-opt the notion of ethos, and by extension the notion of doxa. Ethos allows us to identify solidarity in discourse and its interaction with doxa permits us to explore intended changes in hegemony. At the same time, we acknowledge the importance of power as a core element in the analysis. The shift from ‘power’ to ‘solidarity’ is not about simply changing focus, but rather adding new ones to the analysis. The examples we presented show the flexibility of the notion of ‘solidarity’ even when studying very different social contexts and discourses inscribed in different interdiscursive traditions. Although our examples are only excerpts of isolated texts, they not only hint at the reworking of ethos, but also at the reworking of doxic elements.

A bridge allows for communication in two directions. The re-evaluation of doxa as a dynamic entity lets Critical Discourse analysis integrate ethos on all three levels of discourse, including the higher level of discourse-as-social-practice that accounts for ideological effects and hegemonic processes related to discourse. We are convinced that work within Argumentative Analysis assessing the departure from a purely descriptive stance reveals a common critical and ethical concern with Critical Discourse Analysis. It is also our conviction that re-evaluating doxa in Argumentative Analysis may prove to be a fruitful exercise.

References

Aristotle, translated by Dufour (Médéric), Rhétorique, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1967.

Amossy (Ruth) & Koren (Roselyne), “Argumentation et discours politique”, Mots. Les langages du politique, no 94, November 2010, pp. 13-21.

Amossy (Ruth), La Présentation de soi. Ethos et identité verbale, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, “L’interrogation philosophique”, 2010.

Amossy (Ruth), L’Argumentation dans le discours, Paris, Armand Colin, 2nd ed., 2009 (2006).

Amossy (Ruth), “Ethos at the Crossroads of Disciplines: Rhetoric, Pragmatics, Sociology”, Poetics Today, no 22, Spring 2001, pp. 1-23. DOI : 10.1215/03335372-22-1-1

Amossy (Ruth), “How to Do Things with Doxa: Toward an Analysis of Argumentation in Discourse”, Poetics Today, no 23, Fall 2002, pp. 465-487. DOI : 10.1215/03335372-23-3-465

Amossy (Ruth), La Présentation de soi. Ethos et identité verbale, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, “L’interrogation philosophique”, 2010.

Barthes (Roland), Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes, Paris, Seuil, 1975.

Blommaert (Jan), Discourse. A Critical Introduction, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, “Key Topics in Sociolinguistics”, 2005.

Bourdieu (Pierre), Language and Symbolic Power, translated by G. Raymond and M. Adamson, edited and introduced by John B. Thompson, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1991.

Charaudeau (Patrick) & Maingueneau (Dominique), Dictionnaire d’analyse du discours, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2002.

Charaudeau (Patrick), “Réflexions pour l’analyse du discours populiste”, Mots. Les langages du politique, no 97, November 2011, pp. 101-116.

Chávez Frías (Hugo), “Una cita con el futuro. 12 de febrero de 2009”, in Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información, Las líneas de Chávez. Tomo I. Números 1 a 56. Enero 2009 – Enero 2010, 2010, Caracas, Publicaciones MCI, pp. 52-56.

Chouliaraki (Lilie) & Fairclough (Norman), Discourse in Late Modernity. Rethinking Critical Discourse Analysis, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, “Critical Discourse Analysis”, 1999.

Ducrot (Oswald), Le Dire et le dit, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

EZLN, Comunicado del 12 octubre de 1994, consulted on March 15th 2013, URL: http://palabra.ezln.org.mx/comunicados/1994/1994_10_12_b.htm

Fairclough (Isabela) & Fairclough (Norman), Political Discourse Analysis. A method for Advanced Students, London and New York, Routledge, 2012.

Fairclough (Norman), “A Dialectical-Relational approach to Critical Discourse Analysis”, in Wodak

(Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), eds., Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, London, Sage Publications, 2009 (2001) 2nd ed., « Introducing Qualitative Methods » pp. 162-186.

Fairclough (Norman), “Critical discourse analysis in practice: interpretation, explanation, and the position of the analyst”, in Fairclough (Norman), Language and Power, Harlow, Pearson Education, 2001 (1989) 2nd ed., « Social Life Series », pp. 117-139.

Fairclough (Norman), Discourse and Social Change, Cambridge and Malden, Polity, 1992.

Fairclough (Norman), Language and Power, Harlow, Pearson Education, “Social Life Series”, 2nd ed., 2001 (1989).

DOI : 10.4324/9781315838250

Fairclough (Norman), New Labour, New Language?, London and New York, Routledge, 2000. DOI : 10.4324/9780203131657

Foucault (Michel), L’Ordre du discours, Paris, Gallimard, 1970.

Hymes (Dell), Ethnography, Linguistics, Narrative Inequality . Toward an Understanding of Voice, London and Bristol, Taylor & Francis, “Critical Perspectives on Literacy and Education”, 1996.

Israel (Jonathan I.), Democratic Enlightenment. Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Right. 1750– 1790, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2011.

Laclau (Ernesto), “Why Do Empty Signifiers Matter to Politics?”, in Laclau (Ernesto), Emancipation(s), 2007 (1996), London and New York, Verso, pp. 36-46.

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, 2nd ed., Harlow, Longman, 1992 (1987), pp. 1003.

Maingueneau (Dominique), Le Discours littéraire. Paratopie et scène d’énonciation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2004.

Maingueneau (Dominique), “L’ethos”, in Id., Le Discours littéraire. Paratopie et scène d’énonciation, 2004, Paris, Armand Colin, pp. 203-221.

Maingueneau (Dominique), “L’idéologie: une notion bien embarrassante”, COnTEXTES, n°2, 2007, consulted on March 9th, 2013, URL : http://contextes.revues.org/189. DOI : 10.4000/contextes.189

Maingueneau (Dominique), Dhondt (Reindert) & Martens (David), “Un réseau de concepts.

Entretien avec Dominique Maingueneau au sujet de l’analyse du discours littéraire”, Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferencties, no 8, 2012, pp. 160-187, URL : http://www.interferenceslitteraires.be/node/162.

Meizoz (Jérôme), “Introduction”, COnTEXTES, n°1, 2006, consulted on March 9th 2013, URL : http://contextes.revues.org/83. DOI : 10.4000/contextes.83

Oswick (Cliff) & Richards (David), “Talk in Organizations: Local Conversations, Wider Perspectives”,

Culture and Organization, 10 (2), 2004, pp. 107-123. DOI : 10.1080/14759550420002533404

Perelman (Chaïm), Rhétoriques, Brussels, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 1989.

Perelman (Chaïm) & Olbrechts-Tyteca (Lucie), Traité de l’argumentation. La nouvelle rhétorique, Bruxelles, Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 6th ed., 2008 (1958).

Ramírez (Claudio), “Entre el ethos y la doxa: la literatura en los textos ensayísticos de Hugo Chávez”, in Castilleja (Diana), Eugenia Houvenaghel & Dagmar Vandebosch (eds.), El ensayo hispánico: cruces de géneros, síntesis de formas, Genève, Droz, “Romanica Gandensia”, 2012, pp. 119-129.

Ramírez (Claudio), América Latina en la prensa de calidad flamenca: el caso venezolano (19982006), unpublished Master’s thesis, KU Leuven, 2007.

Steger (Manfred B.), Globalisms. The Great Ideological Struggle of the Twenty-First Century, Landham and Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, “Globalization”, 3rd ed., 2009 (2004).

Vanden Berghe (Kristine), “Intertextualidad y parodia en Don Durito de la Lacandona”, in Id., Narrativa de la rebelión Zapatista. Los relatos del Subcomandante Marcos, Madrid y Frankfurt am Main, Iberoamericana y Vervuert, “Nexos y diferencias”, 2005, pp. 161-193.

Vanden Berghe (Kristine), “Idéologie et critique dans les récits zapatistas du Sous-commandant

Marcos”, COnTEXTES, n°2, 2007, URL: http://contextes.revues.org/208.

DOI : 10.4000/contextes.208

Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), “Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory and Methodology”, in Id. (eds.), Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, London, Sage Publications, “Introducing Qualitative Methods”, 2009 (2001) 2nd ed., pp. 1-33.

Wodak (Ruth), The Discourse of Politics in Action. Politics as Usual, Houndsmill and New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 (2009).

Wodak (Ruth), “What CDA is about – a summary of its history, important concepts and its developments”, in Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael) (eds.), Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi, Sage Publications, “Introducing Qualitative Methods”, 2001, pp. 1-13.

Endnotes

- Fairclough (Norman), Language and Power, Harlow, Pearson Education, “Social Life Series”, 2nd ed., 2001 (1989).

- Wodak (Ruth), “What CDA is about – a summary of its history, important concepts and its developments”, in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), eds., London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi, Sage Publications, “Introducing Qualitative Methods”, 2001, p. 1.

- Bourdieu (Pierre), Language and Symbolic Power, translated by G. Raymond and M. Adamson, edited and introduced by John B. Thompson, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1991.

- Ducrot (Oswald), Le dire et le dit, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1984; Maingueneau (Dominique), “L’ethos”, in Id., Le discours littéraire. Paratopie et scène d’énonciation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2004, pp. 203-221; Amossy (Ruth), La présentation de soi. Ethos et identité verbale, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, “L’interrogation philosophique”, 2010.

- This focus should not be understood as a rejection of the importance of the institutional position as such. For example, works of Maingueneau reformulate some elements of Bourdieu’s theory of field, e.g. “Elle [la sociologie du champ] a beau faire, elle ne peut sortir de l’opposition entre structure et contenu […] Une telle sociologie ne vise pas à articuler les structurations des « contenus », l’énonciation et l’activité de positionnement dans un champ, alors que c’est pourtant là le moteur de l’activité créatrice”, Maingueneau (Dominique), Le Discours littéraire. Paratopie et scène d’énonciation, op. cit., p. 38. For a more elaborated discussion, see Meizoz (Jérôme), “Introduction”, COnTEXTES, n°1, 2006, accessed 9 March 2013, URL: http://contextes.revues.org/83.

- Globalist discourse is a discourse on globalisation promoting a neoliberal variant. See Steger (Manfred B.), Globalisms. The Great Ideological Struggle of the Twenty-First Century, Landham and Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, “Globalization”, 3rd ed., 2009 (2004).

- Fairclough (Norman), op. cit. (supra note 1), p. 167.

- For an up to date overview see: Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), “Critical Discourse Analysis: History, Agenda, Theory and Methodology”, in Id., eds. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, op. cit., pp. 1-33.

- Blommaert (Jan), Discourse. A Critical Introduction, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, “Key Topics in Sociolinguistics”, 2005, p. 27.

- Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), art. cit. (supra note 8), p. 3.

- Blommaert (Jan), op. cit., p. 24.

- Oswick (Cliff) & Richards (David), “Talk in Organizations: Local Conversations, Wider Perspectives”, Culture and Organization, 10 (2), 2004, pp. 107–123, cited in Wodak (Ruth), The Discourse of Politics in Action. Politics as Usual, Houndsmill and New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 (2009), pp. 54.

- Wodak (Ruth) & Meyer (Michael), art. cit. (supra note 8), p. 2.

- Wodak (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 2), p. 1.

- Blommaert (Jan), op. cit., p. 68.

- Hymes (Dell), Ethnography, Linguistics, Narrative Inequality. Toward an Understanding of Voice, London and Bristol, Taylor & Francis, “Critical Perspectives on Literacy and Education”, 1996, p. 65.

- Ibid., p. 70.

- Aristotle, Rhétorique, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1967, cited in Maingueneau (Dominique), op. cit. (supra note 4), p. 204 (the translation is ours).

- Charaudeau (Patrick) & Maingueneau (Dominique), Dictionnaire d’analyse du discours, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2002, p. 239 (the translation is ours).

- Ibid., p. 515 (the translation is ours).

- Amossy (Ruth), “Ethos at the Crossroads of Disciplines: Rhetoric, Pragmatics, Sociology”, Poetics Today, no 22, Spring 2001, p. 1.

- Maingueneau answers Amossy’s critique about his “réticence par rapport à la notion d’ethos [pré-discursif (prior ethos)]”: “Je voulais seulement dire quelque chose qui me paraît de bons sens: pour exploiter efficacement la relation ethos pré-discursif/ethos discursif on doit prendre en compte le genre de discours concerné” Maingueneau (Dominique), Dhondt (Reindert) & Martens (David), “Un réseau de concepts. Entretien avec Dominique Maingueneau au sujet de l’analyse du discours littéraire”, Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferenties, n° 8, 2012, p. 218, URL : http://www.interferenceslitteraires.be/node/162.

- Amossy (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 4), p. 72 (original emphasis, the translation is ours).

- Amossy (Ruth), “How to Do Things with Doxa: Toward an Analysis of Argumentation in Discourse”, Poetics Today, n° 23, Fall 2002, p. 466.

- Amossy (Ruth) & Koren (Roselyne), “Argumentation et discours politique”, Mots. Les langages du politique, no 94, November 2010, p. 18 (the translation is ours).

- The authors do not cite recent work of discourse analysis in the French speaking world.

- Fairclough (Isabela) & Fairclough (Norman), Political Discourse Analysis. A method for Advanced Students, London and New York, Routledge, 2012, p. 242 (original emphasis).

- For example, Charaudeau investigates populism using the concept of ethos, see Charaudeau (Patrick), “Réflexions pour l’analyse du discours populiste”, Mots. Les langages du politique, no 97, November 2011, pp. 101-116.

- Amossy (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 4), p. 159.

- Maingueneau (Dominique), op. cit. (supra note 4), p. 205 (the translation is ours).

- Fairclough (Norman), Discourse and Social Change, Cambridge and Malden, Polity, 1992, pp. 62100.

- Ibid., p. 75.

- Amossy (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 21), p. 8.

- “On constate déjà qu’une bonne part de ce que recouvre traditionnellement la notion d’idéologie se retrouve distribué aujourd’hui sur d’autres notions plus ou moins concurrentes : ‘doxa’, ‘sens commun’, par exemple”, Maingueneau (Dominique), “L’idéologie: une notion bien embarrassante”, COnTEXTES, n°2, 2007, accessed 9 March 2013, URL : http://contextes.revues.org/189.

- Perelman (Chaïm), Rhétoriques, Brussels, Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 1989, p. 362 cited in Amossy (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 21), p. 5 (translated by Amossy, our emphasis).

- Stereotypes are not limited to a negative and deformed representation of ‘the other’, e.g. racist or sexist stereotypes. Stereotypes can also be necessary pre-existing cultural schemes and ready-made images to facilitate the interpretation of reality, a cultural short-cut in order to filter an infinite stream of observations and changing settings.

- Amossy (Ruth), op. cit. (supra note 24), p. 467.

- “La Doxa […], c’est l’Opinion publique, l’Esprit majoritaire, le Consensus petit-burgeois, la Voix du Naturel, la Violence du Préjugé”, Barthes (Roland), Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes, Paris, Seuil, 1975, p. 51, cited in Amossy (Ruth), L’argumentation dans le discours, Paris, Armand Colin, 2nd ed., 2009 (2006), p. 101.

- Amossy (Ruth), Ibid. (the translation is ours).

- Blommaert (Jan), op. cit., p. 30 (our emphasis).

- Amossy (Ruth) & Koren (Roselyne), op .cit., pp. 93, 158 (the translation is ours).

- Laclau (Ernesto), “Why Do Empty Signifiers Matter to Politics?”, in Laclau (Ernesto), Emancipation(s), London and New York, Verso, 2007 (1996), p. 43.

- There are probably as many wordings of definitions as there are dictionaries. We were inspired by the definition from the Longman dictionary because it corresponds with our view on how solidarity is articulated in discourse. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, 2nd ed., Harlow, Longman, 1992 (1987), p. 1003.

- Foucault (Michel), L’Ordre du discours, Paris, Gallimard, 1970, p. 110 (the translation is ours).

- Fairclough (Norman), op. cit. (supra note 31), p. 199. For further discussion about the descriptive, interpretative and/or explanatory character of discourse analysis, we refer to Fairclough (Norman), “Critical discourse analysis in practice: interpretation, explanation, and the position of the analyst”, in Fairclough (Norman), op. cit. (supra note 1), pp. 117-139; the section “2.5 Pros and Cons of CDA” in Blommaert (Jan), op. cit., pp. 31-38; and the section “The Interpretative Process: Understanding and Explanation” in Chouliaraki (Lilie) & Fairclough (Norman), Discourse in Late Modernity. Rethinking Critical Discourse Analysis, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 1999, « Critical Discourse Analysis », pp. 67-69.

- Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional.

- EZLN, Comunicado del 12 octubre de 1994, accessed 15 March 2013, URL: http://palabra.ezln.org.mx/comunicados/1994/1994_10_12_b.htm (the translation is ours).

- After the fall of the last military dictatorship in Venezuela in 1958, the social- and Christiandemocrats (and a minor party that later exited the pact) agreed on the Punto Fijo Pact to share power by in practice excluding other parties.

- Chávez Frías (Hugo), “Una cita con el futuro. 12 de febrero de 2009”, in Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información, Las líneas de Chávez. Tomo I. Números 1 a 56. Enero 2009 – Enero 2010, Caracas, Publicaciones MCI, 2010, p. 52 (the translation is ours).

- As an example of the application of CDA to political discourse, we refer to Fairclough (Norman), New Labour, New Laguage?, London and New York, Routledge, 2000.

- Comité Clandestino Revolucionario Indígena-Comandancia General.

- It could be a coincidence, but even the name of the high Zapatista institution, the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee-General Command, has an ironic ring to it combining the most uncommon “Clandestine” with the more classic and pompous “Committee” and “General Command”.

- For a discussion of post-modernism in the Zapatista discourse we refer to Vanden Berghe (Kristine), “Intertextualidad y parodia en Don Durito de la Lacandona”, in Id., Narrativa de la rebelión Zapatista. Los relatos del Subcomandante Marcos, Madrid y Frankfurt am Main, Iberoamericana y Vervuert, 2005, « Nexos y diferencias », pp. 161-193. See also Vanden Berghe (Kristine), “Idéologie et critique dans les récits zapatistas du Sous-commandant Marcos”, COnTEXTES, n°2, 2007, URL: http://contextes.revues.org/208.

- We refer specifically to the CTV union, the dominant union during the pre-Chávez years and an crucial element of the two-party state system. Chávez’s supporters created the UNT union to counter its influence.

- In fact, several highly placed representatives of this informal coalition of opponents officially supported the far-right military coup against Chávez in 2002 by signing the “Act of Constitution of the Government of Democratic Transition and National Unity” and thus legitimising the new de facto government. Growing massive popular protests in the streets of Caracas and the decision of the majority of the Armed Forces to respect the Constitution, restored Chávez to his function after two days.

- In our research we discovered that this is also the case for some media auto-categorised as progressive, see Ramírez (Claudio), América Latina en la prensa de calidad flamenca: el caso venezolano (1998-2006), unpublished Master’s thesis, KU Leuven, 2007.

- A common trait in many of Chávez’s texts is an ethos based on the values of the Enlightenment, see: Ramírez (Claudio), “Entre el ethos y la doxa: la literatura en los textos ensayísticos de Hugo Chávez”, in Castilleja (Diana), Eugenia Houvenaghel & Dagmar Vandebosch, eds., El ensayo hispánico: cruces de géneros, síntesis de formas, Genève, Droz, 2012, « Romanica Gandensia », pp. 119-129.

- While out of the scope of the example, the discourse of Chávez very often makes reference to the Independence revolutionary Francisco de Miranda, a radical Enlightenment thinker. About radical Enlightenment and democracy we refer to Israel (Jonathan I.), Democratic Enlightenment. Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights. 1750–1790, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 7-8.

Citation

Claudio Ramírez, « Ethos and Critical Discourse Analysis: From Power to Solidarity », COnTEXTES [En ligne], 13 | 2013, mis en ligne le 20 décembre 2013. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/contextes/5805 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/contextes.5805

Copyright License

- Title: “Ethos and Critical Discourse Analysis: From Power to Solidarity”

- Author: “Claudio Ramírez”

- Source: “https://journals.openedition.org/”

- License: “CC BY-NC-SA 4.0”